Classical Mechanics

The big idea #

Encode physics problems as optimization problems on functions.

Newtonian mechanics is about turning physics problems into initial value problems. Given the force laws and the initial configuration of a system, you just crank out the evolution of the system. This is a fully general procedure. Any classical mechanics problem that you can solve with Lagrangians and Hamiltonians you can also solve with forces.

Why is it sometimes better to optimize a function rather than solving an IVP?

Vector calculus is fiddly and easy to mess up. The Newtonian method requires you to solve a differential vector equation, whereas the Lagrangian method encodes all relevant information in a single scalar function. The first approach gives you many more opportunities to make a small mistake.

One can draw a loose analogy to special relativity. The Lorentz transformations are equivalent to the three fundamental effects: time dilation, length contraction, and the rear clock ahead effect. Either one can be derived from the other, but we sometimes prefer the Lorentz method because it gives you fewer chances to slip up. Once you’ve written down the spacetime coordinates of the events you care about, you just put them through the transformations, and you’re done. Plug and chug. No further judgement is required on your part.

Similarly, solving a classical mechanics problem becomes a rote exercise once you’ve written down $ L$ or $ H$ as the case may be. Take derivatives, solve, and put in the initial conditions. Plug and chug. You gain less physical insight than you would from solving N2, but you also run less risk of error.

Newtonian methods don’t generalize to quantum systems. In QM, the position of a particle is described by a wavefunction extending over space, so there’s no well-defined position for you to plug into a force law. It just doesn’t make sense to apply N2 to such a particle, but it does make sense to define an operator $H$ that will govern the system’s motion just like the classical Hamiltonian does. In fact the Schrödinger equation, which is the closest thing in QM to Newton’s Laws, takes nearly the same form as the Hamilton-Jacobi equation. The Lagrangian and Newtonian methods are equivalent within classical mechanics, but when we come to quantum mechanics, it turns out that one method has legs while the other doesn’t.

There are plenty of other analogies between CM and QM. Poisson brackets in CM obey the same (Lie) algebra and have the same physical significance as commutators in QM.

(1)For a classical observable $f$ that doesn’t depend explicitly on time, we have \[\frac{df}{dt} = [f,H].\] For a quantum observable $O$ that doesn’t depend explicitly on time, the Eherenfest theorem says \[ \frac{d}{dt}\langle O \rangle = \langle[O,H]\rangle\big/i\hbar \]

The Feynman path integral has the same form as the classical action. The path of a quantum particle obeys a stationary phase principle just like the motion of a classical system obeys the stationary action principle. Liouville’s Theorem says that if we start out uncertain about the position and momentum of a mechanical system, it can’t evolve into a state whose position and momentum we both know precisely, which is a kind of classical uncertainty principle.

Here’s a hypothesis—It would have been nearly impossible to jump straight from Newtonian mechanics to quantum mechanics, even if all the relevant empirical evidence had arrived early. Imagine a world where all the foundational experiments of QM were performed two centuries early, so that Newton and Leibniz knew about Young’s double slit, Stern-Gerlach, the photoelectric effect, and maybe some other key results as well. In this world, would QM have been discovered and formalized roughly the same way it was in our world, just far ahead of schedule? The answer is probably no. Physics wasn’t just stagnating during two hundred years it spent chewing over classical mechanics. Rather, it was extracting deep lessons, which the founders of QM

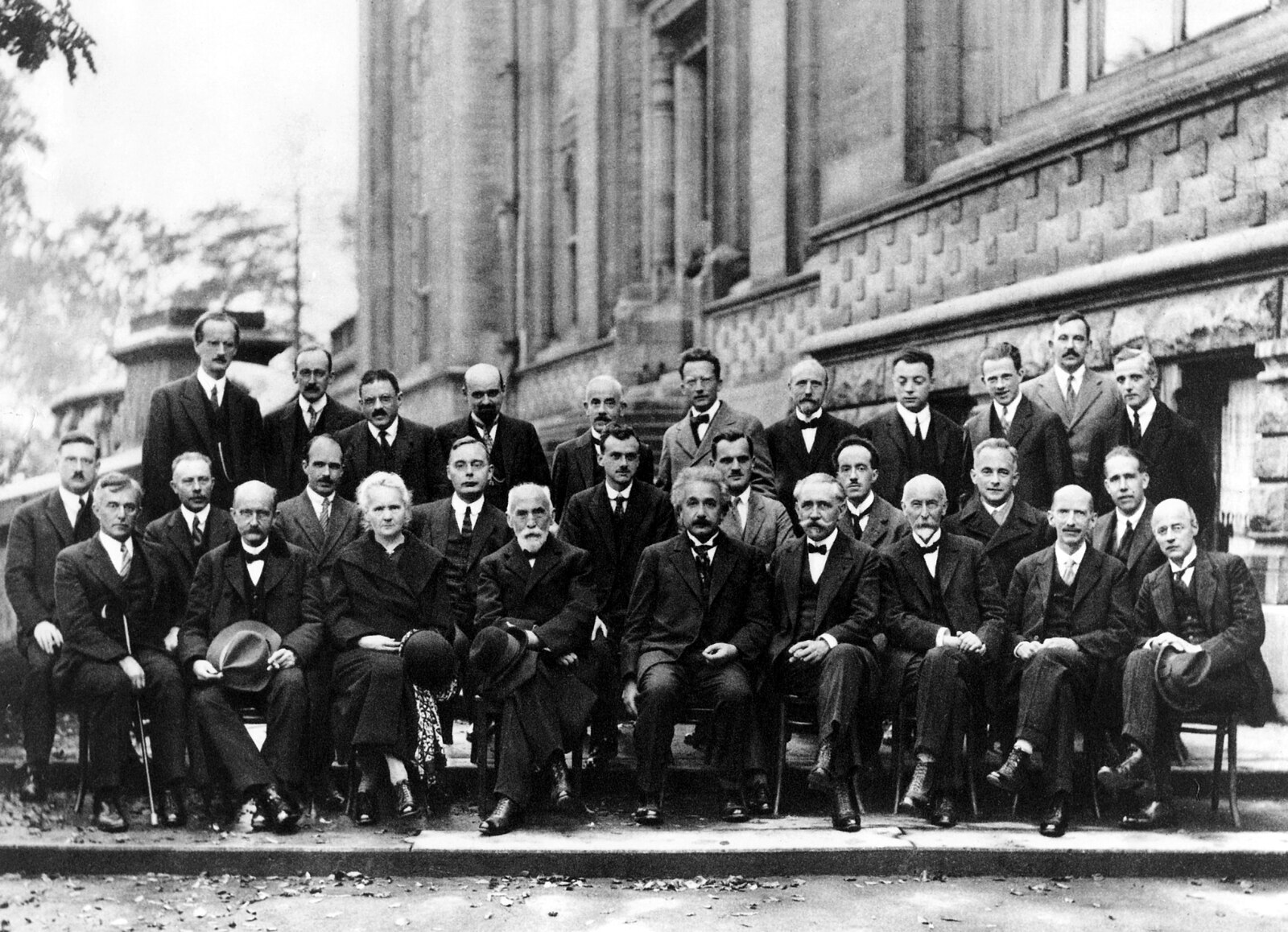

ie, these folks. (The Solvay Conference, courtesy of Wikipedia)

couldn’t possibly have invented on the fly had Hamilton, Lagrange, Poisson and all the rest not gone before.

ie, these folks. (The Solvay Conference, courtesy of Wikipedia)

couldn’t possibly have invented on the fly had Hamilton, Lagrange, Poisson and all the rest not gone before.

Newtonian methods don’t play nicely with relativity. The Lorentz transformation for a force is quite awkward and understanding how to apply it can be rather subtle. If we have to do relativistic dynamics, we’d much rather do them in Lagrangian terms, since the action is Lorentz invariant.

ML makes variational methods very powerful. Obviously this was not one of Lagrange and Hamilton’s motivations when they originally invented their formalizations, but it is a compelling reason for us to study classical mechanics today.

Questions #

- How do we know that there couldn’t be a force that depended on the acceleration of a particle, or on higher derivatives of its position? Relativity…?

- What does Noether’s Theorem really say, and what are all of its assumptions? The loose statement I know—for every symmetry there has to be a conserved quantity—seems shockingly strong.

- Does deep learning raise the status of Lagrangian mechanics, as Alex Alemi suggests in this lecture?

- Can we say anything about how the computational complexity of solving the Euler-Lagrange equations compares to the complexity of solving N2?

- What, if anything, does Hamiltonian MCMC in statistics have to do with Hamiltonian mechanics?

Reading #

Theory

- Landau & Lifshitz, Course of Theoretical Physics, Vol 1: Mechanics. ✔ I don’t tend to like Russian textbooks very much, but this one is beautiful.

- Woodhouse, Introduction to Analytical Dynamics. Goes for rigor over clarity. Woodhouse has a confusing habit of changing coordinates every couple paragraphs.

- Kibble and Berkshire, Classical Mechanics ✔

- Morin, Introduction to Classical Mechanics chapters 6 & 15 ✔ Lives up to Morin’s usual high standards. Very illuminating worked examples.

- Feynman Lectures, lecture II.19 on the Principle of Least Action

- Joseph Conlon’s lecture notes on classical mechanics ✔

Applications

- Denny, “A uniform explanation of all falling chain phenomena” in AJP.

- Gadzinski, “Where is Noether’s Principle in Machine Learning?” ✔

- Norris, “The Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman Equation.” ✔

Last updated 17 January 2025