Paradise Lost by John Milton

I thought I had a handle on PL the first time I read it in 2021, but after a second reading in 2025, I see that I understood nothing. If I'm lucky, I'll mature some more and my Miltonian knowledge again. Then I will look back on me-now and see that he still understood nothing.

There is no end to this process. The reflection may grow brighter, but you never see face to face. Paradise Lost is infinite.

I

PL among epics

The classical epics—really I mean Homer, Virgil, and Ovid—have topic statements. In the first couple lines, they announce what the poem is going to be about. "Rage, goddess" begins the Iliad, and indeed, the main subject of the poem is Achilles's rage. Ovid says he will sing of "bodies changed into new forms," and he delivers. JM gives his epic a topic statement too, and the key word is "disobedience."

Now this is a vexed topic for an antinomian like Milton to take on. He held that all the explicit laws found in both Testaments of scripture had been dissolved into one supreme imperative: to act lovingly, ie, to do everything under the guidance of the Spirit. As Tetrachorodon says, "Our Savior redeemed us to a state above prescriptions by dissolving the whole law into charity." Now the curious thing about disobedience, on the antinomian view, is that it need not be wrong. Indeed disobedience can sometimes be required of a good Christian. If the civil law, the canon law, or even the Decalogue itself tells you to but your conscience tells you -ing would be wrong, the antinomian says obedience to the law would be a sin. (Example: conscientious objection.) So we're reading an epic about disobedience, but we have to judge the morality of disobedience on a case by case basis. Isn't that tricky? We'll want to stay alert to this issue throughout PL.

At least from Virgil onward, epics are national literature. They try to tell you where a people came from and what their defining traits are, and they do this largely by contrasting the protagonist nation with other nations. The Aeneid tells us that Rome began at Troy and that the Romans are pious lawgivers, destined to found a great empire. It shows you this by contrasting the proto-Roman Trojans with the treacherous Greeks and the moody, wrathful Carthaginians. Likewise the Lusiads sets out to tell us who the Portuguese are by contrasting them with the foreign peoples Vasco de Gama meets on his voyages. Tasso's Jerusalem Delivered, which would have been on JM's mind as he sat down to write PL, tries to show you who the Christian Europeans are by contrasting them with the Muslim Arabs.

It's therefore a notable breach of genre conventions that PL is not an English national poem. England and the English aren't mentioned once in the entire opening book, nor are there any English characters anywhere in the poem. Is it a national epic for Christian Europe? Again, no. There are no Christians anywhere in PL until the very end of book XII.

But if we think more creatively, we can recognize the poem as a national epic of sorts. Milton helps us see it. "Say first what cause moved our grand parents in that happy state, favored of heaven so highly, to fall off." (See OED 6, grand = all-inclusive as in "grand total.") Like Virgil telling the story of Pater Aeneas, the father of Rome, JM is going to tell the story of father Adam and mother Eve, the parents of all humankind. So JM is writing an epic about the nation, if you can call it that, encompassing all humans. He's going to tell us where we all came from and what kind of people we all are. How's that for "things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme"?

This poses a problem. We said that national epics explain who the protagonists are by contrasting them with other nations. But if all of humanity belongs the protagonist nation, that would seem to leave no-one else to serve as a foil. JM solves this problem by making Satan and his rebel angels major characters. They are our foils. Like us, they disobeyed their Creator, but for us there is grace whereas for them, none.

The invocation of the Muse—obligatory for an epic—poses special problems for a poet of Milton's religious persuasion. Compare the gymnastics that George Wither went through in Vox Pacifica, claiming inspiration from the Muse, who is really the Holy Spirit, except he's not claiming to be a prophet, but maybe he is one after all. Milton's background commitments are similar to Wither's, but his position is more stable. He comes out and says at the top of Book I that the same Holy Spirit who inspired Moses and David is now speaking through him, dictating PL. What we are about to read is a new book of the Bible.

Revolutionary politics

It's a shocking choice for Milton, the defeated rebel, to show us Satan as a defeated rebel, and moreover, to make Satan's downfall the very first scene of his epic. Here's the most Christian man in all of England spinning a story that implicitly compares him and his revolutionary comrades to Satan and the Baals. This is such a puzzling choice that you might want to claim Milton's hand was forced, that his source material left him no other choice but to compare the defeated revolutionaries to fallen angels. I disagree on three counts.

(1) The Bible didn't force Milton to talk about Satan at all. Milton had an earlier point in his intellectual progression been quite committed to plain reading of scripture, cleansed of superstitious junk and tradition. He had defended this view at great length in his anti-prelatical pamphlets. Now get this—Genesis does not mention Satan. Yes it speaks of a serpent that tempts Eve into eating of the fruit of the tree, but that serpent is never identified in the Bible as Satan, called "the enemy" elsewhere in the Old Testament. The only authority for thinking the serpent was actually the devil is tradition, so by working Satan into the story of the Fall of Man at all, Milton was further betraying his own former position on hermeneutics.

(2) The Bible certainly didn't force Milton to open his poem on the fall of Satan. In fact, Milton has chosen to tell the story back-to-front. The source material he drew upon for the war in Heaven is from Revelations, ie, the last canonical book of the Bible. But Milton moved this war to the very start of Paradise Lost, making Satan’s downfall the spark that triggers the entire narrative. If you have the words of Genesis ringing in your ears, you can also hear an echo of them in I.33-36. Recall, God asks Adam why he tasted of the fruit, and he passes the buck to his wife. She in turn blames the serpent: "The Serpent beguiled me, and I did eat." You hear the same chain of blame in Milton. Like God in the Garden, he asks why man revolted, and transfers the blame to Eve and thence to the serpent. Even the key word "guile" appears. Now, in Genesis, this is the climactic moment. God is about to curse serpent, Eve, and Adam all. But Milton chooses to put the blame game first, and indeed, to run it back farther than the Genesis author does. This is more than mere acquiescence to the source material.

(3) Finally, nothing in the Bible forced Milton to insist so intensely on the parallel between Satan and the defeated Roundheads. Yes, the Bible routinely calls God a king, and so does plenty of Christian writing, but there are other idioms available for talking about God. There's God the Father (which JM will reach for in book III especially), and also God the transcendent being. God the unimaginable is in PL, so we know Milton knew how to write Him that way, but it's not the register he reaches for here in book I. Instead we get "throne and monarchy of God", He who "sole reigning holds the tyranny of Heaven." Over and again, JM calls the fallen angels "rebellious" and speaks of their "revolt" against Heaven's King. The rebel angels' "impious war" is a sophisticated Latin pun on "civil war" = bellum impium. Satan reminds Beëlzebub of the "mutual league" they formed against God, which bears a strong verbal resemblance to the Solemn League and Covenant. Pandemonium is an infernal Palace of Westminster where the demons convene a Parliament. And Hell is depicted as a prison. JM is really clear about this. He uses that exact word "prison," and also calls it a "dungeon horrible" to which "eternal justice" has condemned the routed rebels. You have to remember that Milton himself had been imprisoned not so long ago in the first days of the Stuart Restoration. His description of Hell would have conjured up images of Oxford Castle, the Tower of London, and the old regime's other loathed dungeons.

One way of putting it is that JM has freely chosen, in book I, to pit his politics against his religion. His life's two firmest commitments were to the Good Old Cause and to God, yet here he's contrived a fictional scenario where they come apart, where a revolutionary has to be satanist and a Christian has to be royalist. Why on earth would Milton do that?

II

When we try to judge the debate in Pandemonium and decide which of the demons' arguments hold up the best, we're somewhat stymied by an utter lack of reliable facts. We can't assume a claim is true just because a demon asserts it. As C S Lewis pointed out, the one thing Milton's audience would've known for sure about Satan is that he was a liar. But on the other hand Milton has given us precious little basis for distinguishing truth from lies. Is a renewal of open war against God even possible, or is there no way up to Heaven? We'll belatedly learn in II.885 that war is logistically possible—Hell's gates are wide enough to admit an army—but it's unclear how any party to the debate could know that. Can fallen angels die? Moloch and Belial differ over this. Alastair Fowler confidently asserts that angels cannot die and cites Catholic doctrine to prove it, but we know from Of Prelatical Episcopacy that Milton doesn't accept antique tradition as a reliable source of evidence. If the fallen angels had sued for peace with Heaven, would God have lessened their punishment? Belial and Mammon think so, and no-one ever refutes them, but in book III, it sure seems like God will never forgive the rebels under any circumstance.

Because we have so little firm ground to judge the demons' debate, I think the most productive way to read it is to map it onto a hypothetical debate among the defeated roundheads. Moloch is recommending a second rebellion against the younger Charles Stuart. You can read II.94-8 as saying death would be less bad than subjection to the restored regime. Belial instead wants the former rebels to keep their heads down and obey, lest the king have them executed or persecute them further. Mammon is a bit of a puzzle, because in the end, there's not much daylight between him and Belial. Some clues in Mammon's diction plus the poet's criticism that Belial "counseled ignoble ease and peaceful sloth" in contrast to Mammon make me think the difference is that Mammon wants a return to Jacobean era Puritanism rather than passive compliance with the regime.

But then what is Beëlzebub's position, which ultimately wins out? Here are two of many possible interpretations. Maybe Beëlzebub wants to school the coming generation in republicanism and ultimately seduce them to revolt against the monarchy. Look at how he speaks of humans as God's "darling sons." He calls them "puny," meaning small but also, as Alastair Fowler notes, punning on puis né = born after. All of this language makes us think of children. So perhaps Beëlzebub and his boss Satan (Milton's spokesman) are saying the defeated republicans should carry on their struggle by corrupting the youth!

Here's another interpretation. Notice how many times the demons—but not just the demons—call Earth the "new world." This is a factually accurate description, since book VII will teach us the Earth was created after Heaven and Hell. But the language also suggests Earth is the Americas, and it makes Satan into a colonizer. Book I cast him in the Aeneas role, rallying his troops scattered and adrift after a calamitous supernatural storm. Since Aeneas journeyed west to plant a colony on new shores, maybe Satan will do the same. Notice as well all the navigator/explorer imagery attached to Satan as he voyages through Chaos.

On this new interpretation, we are saying Beëlzebub wants the demonic Roundheads to fight back against the monarchy on a new shore. They'll sail to America and carry on the English Revolution there. One reason this interpretation is plausible is that it actually happened in Milton's lifetime. We know that Milton was personally connected with the Puritan colonies in New England. He was friends with Roger Williams, who even taught JM to speak a native American language. So then is PL the great American epic? Is God King George III and the Fall our War of Independence?

The war in heaven (V & VI)

The big problem of books V and VI is to figure out what the war in heaven is doing in Paradise Lost. Remember, no part of the source material forced Milton to narrate the war in heaven at all. The account he delivers through Raphael is stitched together and extrapolated from details scattered all over Revelations, the Gospels, and the prophetic books of the Old Testament. It's not a straightforward retelling of any Bible story, not like book IX is a sometimes word-for-word retelling of Genesis chapter 3. Milton was making a deliberate choice when he put the war in heaven into PL and when he gave it so much air time.

And a strange choice it was. Raphael's description of the Son riding in glory to subdue the rebels at the end of book VI is horrifying, un-Christian, almost enough to make one turn Satanist. "So spake the Son, and into terror changed his countenance too severe to be beheld, and full of wrath bent on his enemies." A couple dozen lines later, Raphael calls the sight of the Son in his rage "monstrous" and says it was enough to make the rebels jump over the edge into Chaos. This image of God is downright pagan or Jewish. It's like Milton has mistaken God for Jupiter who hurls thunderbolts at his foes, or for YHWH who makes earth crack open and swallow Korah in Numbers. And book VI looks even stranger in hindsight once we get to book IX. There Milton tells us he is "not sedulous by nature to indite wars" because war poems are tedious and empty. If that is really Milton-the-narrator's view, it's very odd that he spent over a thousand lines walking us through the angelic war in full tactical detail.

Here's the best resolution to the problem I've come up with so far. I think Raphael is intentionally exaggerating or speaking in lossy metaphors. We are not supposed to believe the war in heaven unfolded literally as he says it did. How do we know? For one, we know that the Father gave Raphael a rhetorical mission when He sent him to Earth, and it was not to tell Adam about the late war with journalistic accuracy. "Advise him of his happy state," God said, and "warn him to beware he swerve not too secure." So in other words, Raphael is supposed to scare Adam straight. My reading is that Raphael took God's instructions seriously, and so he made up tall tales about a monstrous Messiah and demons crushed alive in their armor beneath hurled mountains all to intimidate Adam into obedience.

A critic might object that an angel would never lie nor stretch the truth. I don't think we can say that. We always have to remember Milton was an antinomian. For him, a seemingly vicious act can be virtuous as long as it's done out of love. Lying to Adam certainly seems vicious, but surely Raphael tells his lies from a place of love. He lies only because he wants to keep Man on the straight and narrow and knows a superhero-movie retelling of the war in heaven is the most effective way to impress on Adam how unwise it is to rebel against God.

VIII

Somewhat like book III, book VIII is split into two approximately equal-length halves. In the first, Adam questions Raphael about whether the heavenly bodies move or the Earth does, and in the second, he tells Raphael about his first memories after being created. Between these two halves, there's a strange shift in Adam's epistemic state.

The first half presents Adam as the original scientist. He has observed the motions of the stars carefully and "compute[d] their magnitudes." Then by the use of reason, he's noticed that something doesn't add up. The stars must move, according to his calculations, impossibly fast if the Earth is to stand still, which seems wasteful to him. It's clear in this speech where Adam's knowledge comes from. It comes from empirical evidence plus an articulable chain of reasoning.

You might expect to see Adam in the second half engaging in the same kind of scientific reasoning, inspecting his environment and arriving at conclusions through legible chains of reasoning. But that's not at all what we get. Instead, Adam makes savant-like inferences about his situation, or else he knows instinctively what it would seem impossible for him to know by evidence. The very first time he opens his mouth to speak, Adam reasons that he was created "not of myself: by some great maker, then, in goodness and in power preeminent." What a leap of logic! How has he spontaneously reconstructed the Cosmological Argument? Or consider Adam's response when God says He needs no companion: "Thou, in Thyself art perfect, and in Thee is no deficiency found…No need that Thou shouldst propagate, already infinite." This is some sophisticated theology coming from a guy who's less than a day old. How has he re-derived the doctrines of divine perfection, self-sufficiency, and infinitude? And when he first sees Eve, how does Adam know to talk about leaving "father and mother" to cleave to one's wife when there has never been a mother nor a father yet in all of history?

Maybe the answer to this puzzle is the same as the moral of book III. We have to trust the Son, not the sun. In the first half of the book, Adam takes sensory evidence too seriously and winds up lost in "Fume, emptiness, fond impertinence." Then in the second half, he just trusts the knowledge God has presumably instilled within him and instantly guesses everything right. Clearly Raphael's last word on astronomy is right, then. It can't matter whether the sun goes round the earth or vice versa, or else God would have created Adam already knowing which it is, just like He created Adam already believing the most important religious doctrines.

The prophetic books (XI & XII)

Indifference of place

I claim a core message of the prophetic books is that places don't matter. God doesn't care about them, and neither should we. None of them are special.

The mountain of Paradise is washed away by the Flood into the Arabian Gulf. It gets denuded of plants and shat upon by sea birds. In a moment of heavy didacticism, Michael explains this was done "to teach thee that God attributes to place no sanctity if none be thither brought by men who there frequent." This is Michael doubling down on a point he made earlier in Book XI, before the prophecy started in earnest. On being told he must leave Paradise, Adam claims to be most afflicted by the loss of a special, spatially-mediated connection to God. Michael replies that in fact, every place is imbued with the divine presence. "Thou know'st Heav'n His and all the earth, not this rock only."

Here Adam is learning a deep Protestant insight. There's nothing special about church buildings. Indeed, it's misleadingly inflationary even to call them churches. They're just meeting houses, or steeple houses. God is in a church no more and no less than he is in any old place. See also the invocation, where JM tells us the Holy Spirit prefers "before all temples the upright heart and pure." God would rather dwell within a true believer than in Solomon's glorious temple or St Paul's stately cathedral.

JM's retelling of the Gospel narrative is completely delocalized. He tells the Christmas story without mentioning Bethlehem once. There is no setpiece entry into Jerusalem, no trial before the Sanhedrin, no march to Calvary. Nor are there any names. Jesus is not named, except proleptically in Michael's retelling of Joshua. Mary is referred to only as "a virgin." Pilate and Herod are not named. The Messiah is "nailed to the cross by his own nation," but that nation Israel is not named. Milton has set the story of Christ's life in a generic location and made all the characters anonymous. Question for another time—Is this kind of delocalization possible in painting? Did the Old Masters set Bible scenes in early modern Europe because their medium does not allow them to elide place as Milton could do in poetry?

The effect of this narrative choice is to universalize the Gospel story. Christ could have lived and walked in your town. He could have been crucified atop that hill on the horizon, just over there. All places are equally a part of his kingdom ("and bound His reign with Earth's wide bounds"). This is something William Blake understood about Milton. Those feet could have walked upon England's mountains green, or anywhere else for that matter. There is no such place as the holy land.

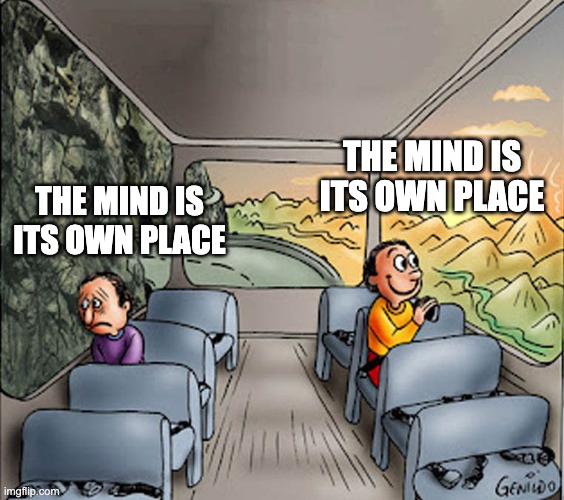

Michael's parting message to Adam is that if he is truly pious and virtuous, his physical banishment from the garden will mean nothing. "Then wilt thou not be loath to leave this Paradise, but shalt possess a paradise within thee, happier far." This is the holy version of a Satanic idea. "The mind is its own place and in itself can make a Heav'n of Hell, a Hell of Heav'n". Satan and Michael are both stating the same truth, but to Satan it's a curse whereas to Adam it's a blessing. If a hot hell always in you burns, you can never escape Hell, but if you have the paradise within, not even a burning sword can force you from Paradise.

Eve actually gets the last word in the whole poem! And she uses it to say she doesn't care where she and Adam go in their exile as long as they're together. "Thou to me art all things under Heaven, all places thou." Again, I read this as rendering literal physical location indifferent. If Eve wants Venice, she can have it in Persia as long as Adam is there with her. Also notice the antimetabole in "With thee to go is to stay here; without thee here to stay is to go hence unwilling." Eve's indifference about place is acted out in the language's indifference about word placement. Go-stay is stay-go.

Indifference of political systems

The prophetic books of PL show us societies with a wide range of political systems, and Michael & Adam pass authoritative judgement on those societies. One might therefore suppose that by reading these books carefully, one can tell what political system Milton thinks is uniquely best. But in fact, it's not so simple as that.

Surely the chief philosophical defender of the regicide and author of the Ready and Easy Way must oppose monarchy. He must think kings are always categorically bad, right?

Exhibit A for the anti-monarchist reading of PL has to be Nimrod, the first king. Nimrod is clearly a malign figure. Michael's description of him rings all the Satan bells. "One shall rise of proud ambitious heart who not content with fair equality, fraternal state, will arrogate dominion undeserved." Reminds me of someone else "ambitious" who attempted "to set himself in glory 'bove his peers." Milton then calls Nimrod a rebel based on the etymology of his name and on the grounds that his pretension to rule makes him a rebel against natural law. This has to make us think of Satan, the most notable rebel in PL. Like Satan, Nimrod has a crew (cf the "horrid crew" of demons). Like Aeneas, and by extension like Satan, Nimrod leads an expansionist campaign westward. Like the rebel angels in VI.510, Nimrod's servants extract minerals from the ground to use in an impious engineering project. "Great laughter was in Heav'n" at their downfall when God casts confusion on their tongues, recalling how the Father has the rebel angels "in derision and secure, laugh'st at their vain designs" in book V. As far as I know, these are the only two times God laughs in PL. Pharaoh is clearly another bad monarch. Michael out and calls him a "lawless tyrant."

But David is also a king. Both in Samuel and in Milton's retelling thereof, King David is chosen by God to save Israel from its enemies, and he does a great job. He "both for piety renowned and puissant deeds, a promise shall receive irrevocable: that his regal throne forever shall endure." Cyrus, who delivers Israel from the Babylonian captivity, is a king. And then of course—this should be familiar to us by now—the Messiah comes to reign as a king.

Milton seems to be telling us monarchy is yet another thing indifferent. Sometimes kings are good; sometimes they're bad. We just can't say in general any more than we can say whether it's good in general to wear a sweater. Sometimes it's cold out and you should wear a sweater; sometimes it's hot and you shouldn't. So too with monarchy. There is a time for God to appoint kings and a time for Him to tear them from their seats

What about non-monarchical political systems? What do the prophetic books say about them? Again, I claim Milton is neither for them nor against them across the board. It's all adiaphora.

Before the flood, there is government by assembly or council. Their system of government doesn't stop them from rejecting Enoch's wise teachings and attempting to silence him by force. Noah also preaches to the assemblies and is ignored. The Hebrews in the wilderness "found their government and their great senate choose through the twelve tribes to rule by laws ordained." So Israel was at that time approximately a constitutional republic with representation for each of the tribes, and Michael says it went well for them. They get right with God. They win battles and destroy kings. They settle the promised land.

If one hadn't read any of his pamphlets and knew only how devout he was, one might naïvely expect Milton to favor theocracy. But he shows theocracy gone horribly wrong in the Second Temple period. The priests get to rule Israel, but "their strife and pollution bring upon the temple itself. At last, they seize the sceptre and regard not David's sons, then lose it to a stranger." Post-apostolic theocracy is an even worse idea, now that the church has been infiltrated by "grievous wolves."

Indifference of time

Walter Benjamin: "Every second of time was the strait gate through which the Messiah might enter." This is, I think, also true in Miltonian time.

Notably absent from the prophetic books' picture of history is progress. Despite being the granddaddy of all Whigs, Milton is no Whig historian. He does not see a long term secular trend out of error and iniquity toward truth and righteousness. Or at least, he doesn't see it here in PL. In Areopagitica it seems he has more patience for the progressive view. See his (rather gruesome) metaphor of the dismembered virgin Truth, whose parts are slowly being put back together. But even there, JM says Truth will not be fully reassembled "till her Master's second coming." We humans can make some progress, but God will have to do the greater part. Compare a standard Protestant view of soteriology: Virtue counts in your favor, but the bulk of your sin will have to be cleared by the grace God grants you unearned.

Milton's history is stagnant and cyclical. Every age of justice is followed by an age of apostasy until another Christ-type comes to restore justice, and the cycle repeats. Adam and Eve set forth on their exile having learned to love and obey the Lord, but their son commits the first murder. Cain's descendants become the pious sons of God, but then they are tempted into the tents of wickedness. The Flood wipes out all men except the godly Noah, whose descendants enjoy a golden age. But then Nimrod rises and reigns a tyrant. And so on, and so on. Even after Christ intervenes in history, the cycle still doesn't end. The apostolic church is corrupted by wolves and inward piety is displaced by outward forms.

On this view, what's the point of studying history? Why bother to watch the waves crash when the tide stays put? Here are two Miltonian answers, which may complement one another.

(1) You watch the waves because you want a preview of the tsunami you know is coming. This is in some sense Michael's official answer. Through Moses, God informed the Hebrews "by types and shadows of that destined seed to bruise the serpent, by what means he shall achieve mankind's deliverance." In other words, Moses is a sort of proto-Christ, sent by God to act out in miniature what the Son's coming will be like. Even Christ's first coming in humility to work an invisible victory is just a preview of his second coming in glory to triumph unmistakably. ("And all flesh shall see it together.")

(2) You watch the waves so that when you find yourself smashed beneath the surf, you can meet the situation with equanimity. At every turn in Michael's story, Adam keeps overreacting to the latest plot point. Michael shows him the ravages of disease, and he falls into Job-like despondency. "Why is life giv'n to be thus wrested from us… who, if we knew what we receive, would either not accept life offered or soon beg to lay it down, glad to be so dismissed in peace." But this lamentation turns out to be premature when Michael corrects Adam, telling him death need not be painful. Next Adam sees metalworking and the courtship of the sons of god and daughters of man, and he likes what he sees. "Here nature seems fulfilled in all her ends," he says, as though the corruption of the Fall were already undone. This time Michael warns him not to trust too much his impressions of goodness or badness. "Judge not what is best by pleasure, though to nature seeming meet."

I'm reminded of a Taoist parable where a farmer loses his horse, and the neighbors say "Terrible!" Then the horse comes back at the head of a herd, and the neighbors say "Wonderful!" Then the farmer's son falls off the horse and breaks his leg, and the neighbors say "Terrible!" Then the press gang comes to recruit soldiers and they let the farmer's son off on account of his broken leg, and the neighbors say "Wonderful!" The causal chain keeps going. At some point, you want the neighbors to do induction and stop overreacting. One just can't know whether the news is good or bad til all its consequences play out, and in the end, the news will probably be indifferent.

This is the lesson Michael teaches Adam. You don't want to flip-flop between praising God and wishing He'd never set the world in motion with each turn of history's wheel. God's ways are always justified, regardless of how things look from your limited, local human perspective. This explains why the defeated Milton might have chosen to retell all of world history at the end of PL. Perhaps he was reassuring himself that the collapse of the Commonwealth was just another of history's regular downswings. Defeat is never permanent. Another wave will always come until the wave of the Apocalypse sweeps everything away.

My thinking on Paradise Lost has been heavily influenced by Christian Thorne, whose seminar on Milton I took at Williams in fall 2025.