Book Bounties

Most books that I would like to read have not yet been written. They exist, in some Platonic sense, out there in the library of Babel, but no-one has bothered yet to summon them into our world. That's a real shame.

I will try to incentivize some of the unwritten books I most want to read into existence by posting bounties for them. If you know that one of the books described below has actually already been written, send me the title and author, and I'll give you a shoutout on this page. If you write one of the books described below (with or without the help of AI), I promise to buy a copy, and I will give your book an acknowledgement. If you would like to boost one of my bounties by pledging that you too will buy a copy of the unwritten book, send me a message, and I'll add your name below.[1]

Matthijs Maas boosts both of the bounties below.

A history of Wagner Group's rise and fall

Wagner Group is a Russian mercenary army active since roughly 2014. They're notorious for fighting in the Russo-Ukrainian War and the Syrian Civil War, among other conflicts. They also came very close to overthrowing the Putin regime in summer 2023. Wagner's leader Yevgeny Prigozhin all but declared war on Moscow in a social media video, then marched his troops from the front to within 200 miles of the capital. But then the rebellion evaporated, apparently thanks to a settlement brokered by Alexandr Lukashenko. Prigozhin went into exile in Belarus for about two months before being killed in a plane crash. Wagner troops were reportedly pulled out of Ukraine. It seemed like the end of the road for Wagner, except that two years later they're still somehow causing trouble in Mali.

I'm interested in the Wagner Group's history because of what it says both about modern Russia and about dictatorships in general. What kind of state allows a loose cannon like Prighozin to mass a 50 thousand-strong private army and then fails to infiltrate it with state security?[2] Why was the Putin regime so catastrophically unprepared for the Wagner revolt? All of this clashes with my models of Russia and Putin. Isn't all of Russia under extremely tight state control and constant surveillance? How did Putin, so famously paranoid, not do more to stop Wagner from revolting in the first place?

I also have questions about how the revolt ended. Could Prigozhin really have believed that the terms of the deal would be honored and he would get to live? It's hard to believe he could have been so naïve, especially since the day after Wagner stood down, prediction markets gave him a chance of being killed within the year. So there must have been more to the Wagner-Putin deal than was publicly announced, right? The Telegraph claimed that Wagner really backed down because some of their leaders' families were in state custody and Putin threatened to tortue them, but no independent sources have confirmed this story. Is it true?

What does this whole episode teach us about the game theory of powergrabs? At the time that Prighozin declared his revolt,Tyler Cowen predicted that he or Putin had to die within a week; there was no other stable equilibrium. In the event, it took more than a week, but I do think the spirit of Cowen's prediction was right. When is another stable equilibrium possible? In other words, when can you back down from a coup peacefully and survive? It seems like it would be in rulers' own interest (at least on some margins) to create more credible off-ramps for rebels so that they don't fight to the death.[3]

The best author to write this book should be a Russophone, an experienced Putin watcher, and a competent investigative journalist. They should at least consult a scholar of coups and maybe they'd even be one. A hypothetical sum of Masha Gessen and Naunihal Singh would be well qualified to write the book that I'm looking for.

A history of genomic progress

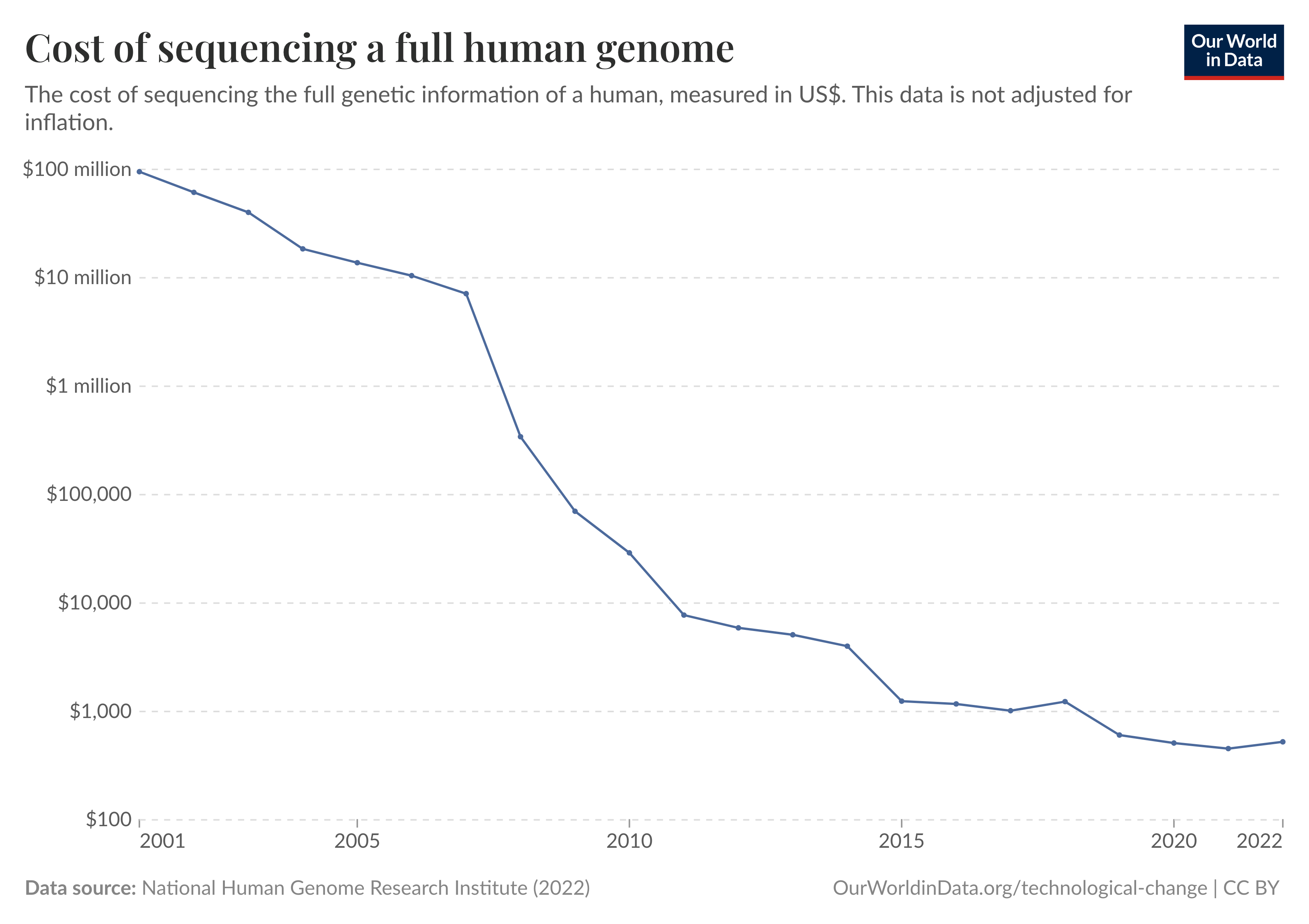

There's an epic story waiting to be told about how this happened.[4]

In twenty years, we cut the cost of sequencing a human genome by more than five orders of magnitude! And this feat is even more impressive if you look farther back in time. The first nucleic acid ever sequenced (by Robert Holley and others in 1965) was 76 nucleotides long and took 15 person-years to sequence. So if you had sequenced a full human genome in 1965 using Holley's methods, the labor cost alone would have been about 10 teradollars.[5]

Some authors have already tried to tell the story of how sequencing costs plummetted. For instance, Jay Shendure and others have a nice paper called "DNA sequencing at 40," where they recount the history of DNA sequencing technologies from the seventies to 2017. James Heather and Benjamin Chain's "The sequence of sequencers" covers roughly the same scope at a more comfortable pace. These papers are both pretty good, but I have three major complaints about them. (1) They're written for specialists. Unglossed biology jargon is everywhere, and when new sequencing methods are introduced, the authors don't do much to help readers picture what's happening physically. (2) They're out of date. Shendure & al.'s history of sequencing—the most recent high quality paper I could find—is eight years old, so it can't discuss important recent advances in paleogenomics, single-cell genomics, and probably other subfields of genomics I'm not aware of. (3) Neither paper presents a unified thesis on how sequencing got cheap. Instead, they give us a mosaic of incremental innovations and leave us to figure out how they all added up to ten OOMs of progress.

I see an opening here for someone to write the history of genomic progress. It should be sophisticated but accessible to non-experts with only college freshman level science knowledge. It should cover all the key innovations in nucleic acid sequencing technology up to 2025 and explain them on a physical level. And it should have one foot in economics so that it can answer the big question: How did sequencing get so cheap? Sarah Constantin has already taken an admirable swing at this one in her essay on "The Enchippening." She argues that sequencing got cheap by riding semiconductor manufacturing's coattails. The flow cells and photodetectors that make up the core of a modern DNA sequencer are made with the same methods we use to make computer chips, so as those methods have gotten exponentially better, sequencing has naturally gotten exponentially cheaper. I want to know how well this story holds up when you take a close look at the history of sequencing. When exactly did we start to enchipen sequencing, and was there really a dramatic change in the rate of progress at that point? What are the most important drivers of genomic progress besides the enchippening?

This book calls for a special author. They must be enough of a scientist to really understand how sequencing works (and has worked), but they also need some of the skills of an economist and a historian. The ideal author might be Saloni Dattani, James Somers, or some obscure guy living in Cambridge, Massachusetts who's seen the whole history of genomics firsthand and knows the field inside and out.

Bonus: Books that could use some midwifery

Here are some books that are already partially written but could use some help coming into the world. If you're in a position to help get them finished and published, I urge you to do so.

Caspar Hare has announced that he has a book under contract "about whether big theories in physics, cosmology and metaphysics have a bearing on what we ought to believe about ordinary, common-or-garden things, and on what we ought to do in ordinary, common-or-garden contexts. I say they do." What an interesting and important thesis. As someone above the 99th percentile in time spent thinking about big theories in physics, cosmology, and metaphysics, I have awaited this book eagerly. But more than five years have passed since Hare first announced it, and there is still no book. Rumor says it may never be published.

Bentham's Bulldog: I think sometimes facts that we might change our mind about should affect what we think about things.

Daniel Muñoz: Caspar Hare has written a brilliant defense of this view in his masterpiece, Living in a Strange World. Unfortunately, the world will never read it, because Caspar is too lazy to write the blurb for the back cover.

Anders Sandberg is working on a massively learned book about what a technologically mature civilization could achieve within our universe's ultimate limits. It's called Grand Futures. Sandberg has previewed the book's ideas in a lengthy interview with Rob Wiblin, and it has a glowing review from the not easily impressed Gavin Leech. I've read a manuscript of Grand Futures from 2022, and I can confirm it lives up to the hype. Now I want Sandberg to finish the many TODOs that tease readers of his manuscript and get the great work published so it can be read and discussed more widely.

Richard Moran, maker lucid of authors abstruse, says he's writing a book on Marcel Proust. I have no particular reason to fear this book will fail to be born besides Moran's age. I do hope he finishes it in time. His essay "Kant, Proust, and the Appeal of Beauty" is the most insightful commentary I've read on art in La Recherche—better than this and this—and I want to read more where that came from.

| [1] | You can reach me at milesmkodama at Google's mail. |

| [2] | Or so military historian Kamil Galeev claims in his excellent ChinaTalk interview. |

| [3] | Cf The Art of War chapter 7.3: "When you surround an army, leave an outlet free." |

| [4] | From Our World in Data using data from the National Human Genome Research Institute. |

| [5] | I got this by assuming a Cornell professor made 20 kilodollars per year in 1965, so the labor cost per nucleotide would be 4 kilodollars. Multiplying by the 3 giganucleotides in the human genome gives us our ballpark answer. |